When perimenopause meets ADHD

Part 1: in which a Work Fart is managed with panache and grace due to a neurobiology primed for crisis

Comrades, my lovely Mum died three weeks ago, and I’m processing all the different aspects of that; the expected feelings as well as the curveballs. I will write about it. I don’t know when. I don’t know how yet.

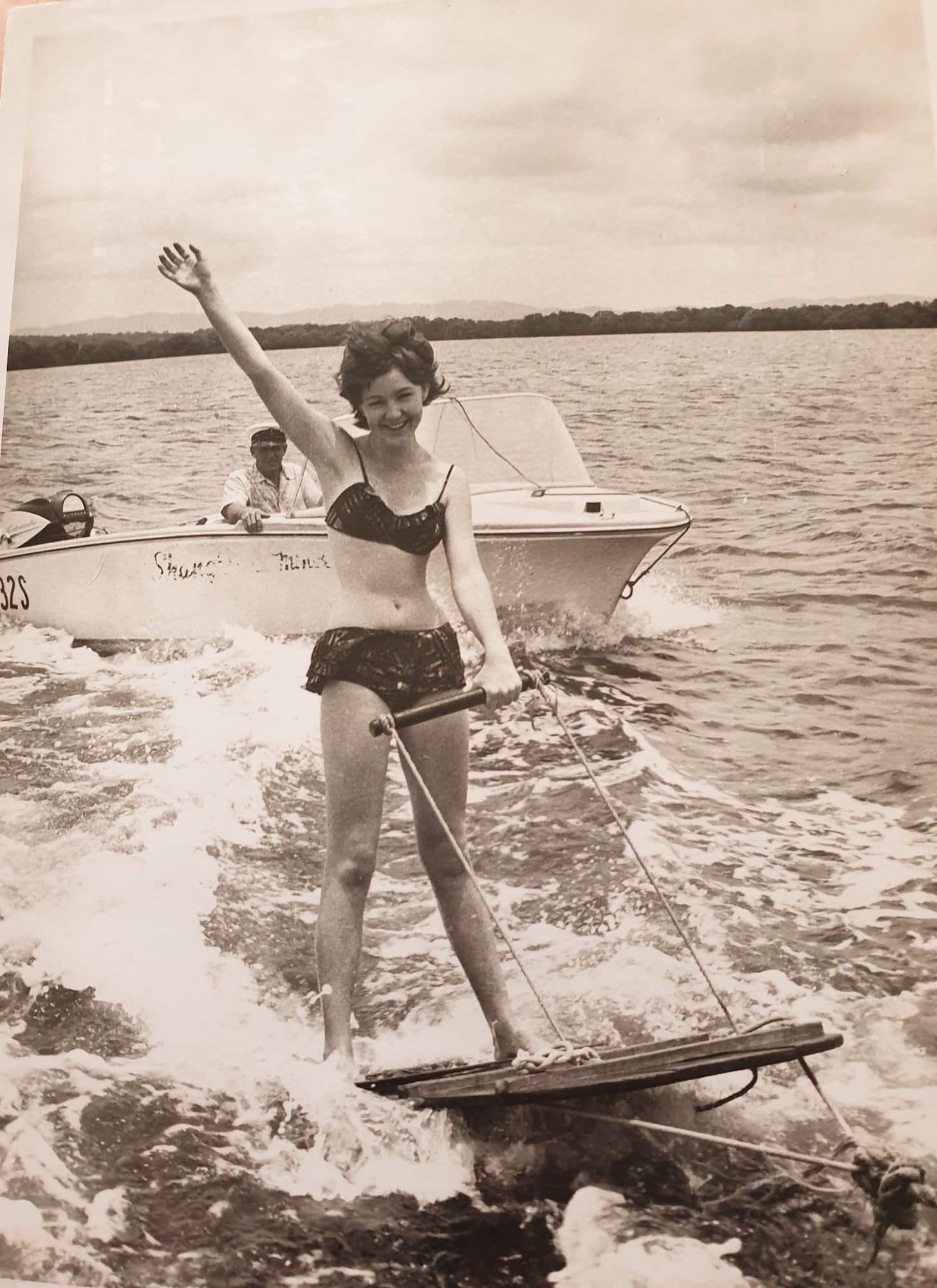

Off she goes, through the spray, young and beautiful, and trailed by a happy Captain. Until I can frame my thoughts about the recent past, I’m going to share something else: the start of a small series about ADHD.

Give Them a Little Fart

During the year I turned fifty, I was away for work, delivering a training program to a room full of people when, without warning, I emitted a squeaky, unmistakable little fart. One might expect that in this professional position, and at this dignified life stage, I might have had the wherewithal to sail on, leaving the attendees wondering ‘Did that just happen? Surely not.’ Sadly, poise isn’t a quality I possess.

‘Oh!’ I said, as surprised by the little bottom burp as my attendees were. ‘I beg your pardon!’

There was a moment of silence that stretched a thousand years, and then, ‘Let me draw your attention to this next slide,’ I continued, smoothly.

The rest of the workshop continued with no unexpected surprises although I could no longer make eye contact with the first three rows. When I got back to my shabby motel, I texted the story to my husband Keith and my WhatsApp group-chats, who were all delighted, as was, I’m sure, every student who took the anecdote home to the dinner table. What’s a little dignity in the face of a good story?

But then I sank back on the scratchy bedspread and felt a familiar overwhelm wash in: the grinding hip pain and sharp headache; the jittery anxiety, the crisis of confidence and the tidal pull of fatigue underlying it all. That year I sought treatment for my symptoms and received two life-changing diagnoses. Perimenopause, meet ADHD. Let the games begin!

Before my diagnoses, like most people I knew, I was juggling a lot of balls. Mine included three children grappling with a pandemic-tinted adolescence, two elderly parents in perpetual crises of ill-health, a part-time job in trauma training (very scene of the Work Fart), volunteer work on a suicide hotline and at the local school, and edits due on my first book as it neared its publication date. For a long time, I kept all those balls in their air with lists and master lists and mental arithmetic; a steady diet of caffeine and stress, but as I approached fifty, these strategies stopped working.

It was through a process of searching for help for some of my teenagers struggles that ADHD crossed my path for the first time. Despite having a Master’s degree in counselling and working off and on for many years in health, I only knew ADHD as a behavioural label for little boys bouncing off classroom walls. The idea of it in relation to my own way of operating had never, ever crossed my path. But we were in a cultural moment that was recognising that ADHD presented in women with a set of symptoms that were recognisably different to the long-held wisdom.

Lightbulb after lightbulb flamed in front of me, painfully bright, like they had been there, hiding in plain sight, the whole time.

Lightbulb: an online test for women; Do you feel like you're always at one end of a deregulated activity spectrum — either a couch potato or a tornado? Do requests for "one more thing" at the end of the day put you over the top emotionally? Do you hesitate to have people over to your house because you’re ashamed of the mess? Do you have trouble balancing your finances?

Yes, of course. But doesn’t everybody?

Pause. Doesn’t everybody, really?

Lightbulb: a description of ‘internal hyperactivity’ and its symptoms often applied to ‘social’ girls: Talks excessively. Fidgets and often needs to get up and walk around. Acts impulsivity or speaks before thinking.

Lightbulb: An outline of the common experience of those with unmedicated ADHD having four or five things happening in their minds at once, including music.

Lightbulb: The common thread of ADHD girls and school reports: Could do better. Isn’t reaching her potential. If only she could focus. If only she could settle. If only she. If only she.

My eyes burned. Every symptom list, every Reddit thread, every Internet assessment questionnaire cut incisively, surgically close to the bone. I had never seen my own idiosyncratic difficulties so neatly summed up, and so specifically, from the small to the large: my habit of unconsciously playing constant musical notes on my fingers? ADHD. My inability to sit normally on a chair? ADHD. My nail-biting? ADHD. ADHD. Job history? Academic history? Relationship history? A sense of chaos that seemed to hover over me, like an individual thundercloud over a hapless sap in a comic strip? ADHD. ADHD. ADHD.

There is a dismantling of self that comes with this kind of a late-life relabelling. As I entered a life-stage in which my hormones took charge of the wheel, I simultaneously learned that my brain had a structural difference that impacted significantly on how I functioned, and always had.

The always had took a beat to absorb. Perimenopause was a new situation, but my inherited and high treatable neurobiological condition of ADHD had gone undiagnosed for five decades. A camera panned out at dizzying speed so that I was suddenly viewing a whole life, from childhood to middle age, from a novel angle. My difficulties with time, from struggles in-the-moment to an inability to conceptualise the future. My many near-escapes, impulsive decisions and shenanigans. My roles as mother-of-three, as wife, daughter, friend. The very core idea of who I was. I processed the gravity of this as I leaked estrogen like a popped balloon.

Some internal tectonic plate shifted. All my ideas about myself were up for review. I had entered a cerebral room of scattered papers, and ADHD was like being handed a cabinet to file them all. The patterns of ADHD shone an explanatory, interrogative light on challenges I had long regarded as moral failings and character flaws, as an inability to manage certain grown-up aspects of life and as an essential ‘difference’ to others, who seemed to live with a steadier ground beneath their feet.

The idea that this constellation of symptoms incorporating impulsiveness, distraction, poor memory, a lack of focus and a tendency to burn hard and then collapse could all be attributable, to some degree, to a specific neurological dysfunction was mind-blowing. A bio-mechanical or psychiatric issue, rather than a temperamental flaw? I’m not incapable? I’m just mental? Stop the press: if I have ADHD, does that mean nothing is my fault anymore? It’s not me, I long to get printed on a t-shirt. It’s my underactive left inferior orbital prefrontal cortex!

The whole thing felt, of course, like a fake-out, a bait-and-switch, an easy pass. I wrestled with it. The world was in collapse and everybody in it was struggling with focus and attention. Was I so desperate for a tidy answer that I was avoiding some deeper truth? Could all of this not be explained by menopause? Depression? The mental load? Motherhood? The pandemic? The pain-of-the-earth that the Germans call weltshmerz? Maybe I just needed to give up gluten, or glucose, or immerse myself daily in ice water. Could I not just fix it all with a Master-Master List in a lovely fresh notebook? What was next, a flesh-eating brain parasite that explained why I’d rather watch Ladette to Lady on YouTube than fold the laundry? A nifty fungal ear infection that explained why I didn’t hear the alarm on my phone? Or, more precisely, the 897 alarms? (ADHD.)

In truth, the intersection of perimenopause and undiagnosed ADHD can make quite a big mess. Perimenopause is a medical transition, with complex physical impacts, including cognitive ones, while ADHD is a psychiatric anomaly (or alternative neurotype, depending on your preferred definition) that affects the brains’ ability to focus, manage distraction and process information. They are separate, but they affect each other intensely, and not very usefully, like JLo and Ben. Declining estrogen levels can impact dopamine function, exacerbating ADHD symptoms, and issues with memory and anxiety and sleep occur in both conditions. Basically, perimenopause makes ADHD worse, and adds some extra weird stuff on top. Fun!

This is why it can start to seem like every middle-aged woman you know has ADHD. (Also, like wild dogs, neurodivergents travel in packs, so we unconsciously seek each other out for the oversharing and the good stories.) It can mark a point at which untreated ADHD that has previously been managed with white-knuckling and Master Lists becomes impossible to manage; often just when we are expected to care both ‘up and down’ to meet the needs of children as well as aging parents.

Diagnosis is a grind. Establishing perimenopause involves a lot of symptom-tracking and blood tests, while ADHD diagnosis is a beast: a protracted and gruelling process of psychiatric assessment that aims to rule out, one by one, all other possible explanations. Clinical diagnosis of ADHD requires a ‘longitudinal picture’ from childhood that shows symptoms across the life span. For me, this was as clear as an arrow to the heart. It was a confronting diagnosis, but a useful one, clarifying many challenges I had long faced, and containing the gift of grace. It sparked a profound shift away from self-blame to self-compassion.

In the two years since diagnosis, meds have helped me enormously, both HRT for perimenopause symptoms as well as the psychiatric meds that balance out the underperforming chemistry of my ADHD brain. But the strategies I’ve developed, and the way I’ve come to understand myself, have been the greatest gift to me. Rather than shame, I’ve come to feel appreciation for my neurodivergent brain and the wisdom of mid-life.

My ADHD, having inoculated me against humiliation through a lifetime’s worth of shameful incidents and stuff-ups, is why my brain so quickly coped with the horrors of the Work Fart, skated smoothly through the professional emergency, and alchemised the whole thing into comedy. And by perimenopause, women have seen a bit of everything. They know that many worries can be solved by drinking a glass of water and sitting on the toilet for a bit. The combination of the two might be complicated, but it keeps life interesting. After that infamous training session, every time I left on a work trip, Keith would say ‘Good luck honey. Give them a little fart.’

This is the first in an ADHD series I will publish here on Substack, interspersed with the intermittent writing and Port-a-Loo content you’ve come to expect. I’m going to try and unscramble the egg for myself, looking at the neurobiology of ADHD, the impact of the ADHD tax, the idea of executive function, how ADHD interacts with menopause and what role in plays in work and creativity. I’ll ask the big questions: if ADHD really is a superpower, why can’t I fly yet, goddamit? And also, see that cat over there? Do you think it looks like a rat? Did you know a group of rats is called a mischief? Did I ever I tell you about the time a rat ate the gusset of my friend’s underpants? Sorry. Sorry. Sorry.

Comrades, share with friends if you think they might relate. Send me interesting links. Most of all, tell me about the time you gave them a little fart.

Books and Resources

Just a few.

The Menopause Manifesto by Jen Gunter

The Year I Met My Brain by Matilda Boseley

Driven to Distraction by Ed Hallowell

Em Rusciano’s wonderful pod Anomolous

Holly Wainwrights wonderful pod Mid

So well written. And so many parallels with my experience! And LOVE the fart story. I’ve often wondered why I seem to have a deficiency in the area of shame but it’s one of the things I’m so grateful due to a great deal of rebellion domaine seeking behaviour when younger too! I’m getting assessed for ASD as it runs in the family and is comorbid (and I have many other sensitivities and behaviours and family history) and find myself now internally investigating which part of me drives certain habits and behaviours (and unlearning the unhelpful ones that aren’t related to either). It’s been a process and a discovery that has finally led to self acceptance and inner peace for me. Thank you for the read. ☺️

I loved reading this! “A group of rats is called a mischief”. That sounds like me and my friends!