Audio listeners, enjoy the appearance of naughty Biggles towards the end.

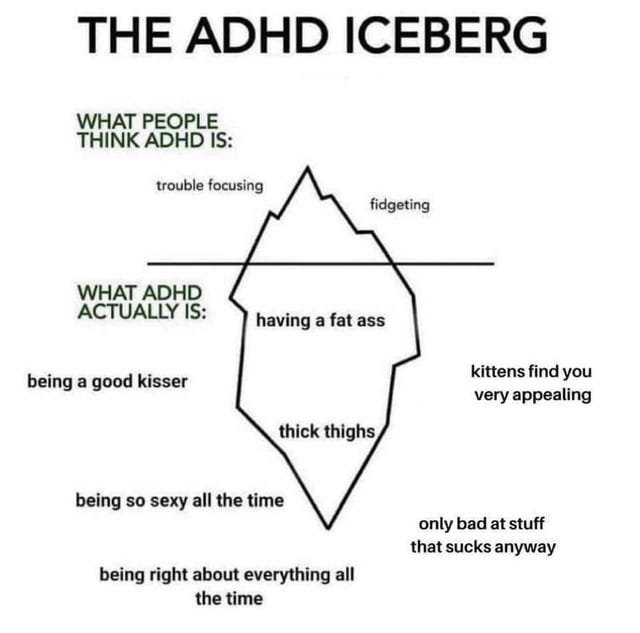

Let’s start with the best ADHD meme in the known universe.

And my boyfriend Phil Dunphy in one of the best representations I’ve seen on TV.

A caveat: this newsletter explores the neurobiology of ADHD from an amateur perspective; the brain-science version of ‘I’m not a gynaecologist but I can take a look’ from my first ADHD file (read it here.) As in, I’m not a neuroscientist but I’ll have a crack (is there a proctologist joke I’m missing here?) I digress! Blame my underactive left inferior orbital prefrontal cortex!

In short: this newsletter is me trying to figure some stuff out, and taking my internet friends along for the ride. If you’re going to act on medical advice from a lightly comedic Substack, then all I can say is: bold choice. Mazel tov!

Let’s dive in.

When first diagnosed with the ‘fun at parties’ neurotype, I was drawn to the science of the thing, and trying to understand the neurobiology of ADHD took me down a wild path. ADHD expresses itself in a bursting firework of different patterns in every person, and there is no one definitive blood test or brain anomaly that clarifies exactly what’s going on.

Neuroscience is fascinating and frustrating. I find myself grasping the head of the snake while the tail slithers out of my grasp. How can we know so much about the brain, and at the same time know so little? There’s not a single, unifying theory of how the brain works, for instance. But there is a lot of really interesting work going on that tries to unpack and understand ADHD, variously called a 'neurodevelopmental disorder’, a ‘disability’, a ‘neurotype’ or a ‘superpower’, depending on whether you wear a cardigan or not. Regardless of the label you prefer, ADHD is highly correlated with being both funny and sexy. And although it is expressed behaviourally, ADHD is a brain anomaly.

So how does ADHD affect these lumps of mashed potato between our ears?

Most of the action is located in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain located behind the forehead. Let’s think of the prefrontal cortex (the PFC) as Britney, the door bitch of a hot nightclub called Brain. She has a few jobs. To run Brain, Britney needs to pay attention to what’s important, avoid distractions, adapt to change and remember what’s going on. She’s also in charge of the vibe; managing personality expression and social appropriateness. She processes info about the stimulus in front of her (the queue) and sends action-orders out to other parts of Brain. In short, Britney runs the executive function of Brain. Nobody gets in past Britney.

We should imagine Britney as a sort of David Bowie crossed with Kate Hepburn figure, sporting an ear mic, and possibly a cane. Britney scans the queue, choosing where to send her resources. Which stimulus goes straight under the velvet rope to the VIP room and which one goes to the back of the line? Britney focuses our attention: there’s Leo DiCaprio, hand-in-hand with Dame Judi Dench. Through you go, Your Grace! Leo gets a wink of approval. Normcore Tanya from accounts doesn’t even register on Britney’s radar.

A vital function of the PFC is the ability to retain focus on things that are boring in the moment, but have longer-term importance. To do this, Britney has to block internal and external distractions, suppressing irrelevant stimuli. Tanya is really pushing to get in, arguing the importance of the week-end-financials, but to focus on Tanya, Britney must ignore the sight of Leo and Dame Judi really going for it, sexually, in the corner.

Once Britney has decided what to do in any given moment, she sends her orders through to other rooms in Brain for action. Britney’s orders travel through networks of neurons that interact with each other through synapses on dendritic spines. Basically, electrical signals are spat from one neuron to the next, like messages shouted down the line at an Occupy event.

These signals travel to the basal ganglia (the VIP room) through a mechanism called the thalamus gate. Let’s imagine this as the velvet rope that Britney is lifting to allow or block messages into Brain. Unfortunately, ADHD brains have a weak thalamus gate; a kind of knot in the velvet rope; a fraying thread; a fault in the fabric, and this means they sometimes a person with ADHD cannot stop themselves from blurting out a problematic comment or engaging in risky behaviours. We are fun at parties, to be fair.

The velvet rope is crucial to the smooth operation of Brain, because visual and auditory information as well as messages about memory, emotional behaviour and motor function are all sent via the thalamus gate. The thalamus also manages ‘somatosensory’ function (or the understanding of a sensation), so a creaky thalamus gate can also explain why many people with ADHD also have sensory processing disorders.

In a neurotypical brain, a functional thalamus gate gives a person nifty extra micro-sends of time to consider an action. These micro-seconds can build up over a lifetime to paint a starkly different picture between the ADHD and the non-ADHD brain on many, many measures of quality of life. This is sometimes called the ‘ADHD tax’: a subject for another newsletter.

Clinician Russel Barkley calls ADHD a ‘performance disorder’. Britney knows what needs to be done (line up the Cosmos! Set up the limbo pole! I haven’t been to a nightclub for a while) and the ‘knowledge-holding’ areas of Brain know how to do them. But the messages just aren’t getting through. The functioning of Brain starts to get messy, and as Britney gets stressed, the operation of Brain just gets messier.

Barkley’s ‘performance disorder’ notion explains why people with ADHD can have the knowledge they need – strategies, plans, notebooks (so many notebooks) - but still be unable to activate those plans. Task-starting can be a real sticking point; with procrastination reaching a clinical level. It’s why ‘pills’ and ‘skills can intersect so effectively in ADHD management. Pills don’t teach skills. But without the pills regulating the mechanical function of the brain, the skills don’t stick.

Now Britney, peering frantically through her glasses at a scribbled-over clipboard, is a busy lady. She has to regulate emotion on top of everything else, as the ventromedial portion of the PFC sends signals to the amygdala and the hypothalamus, the areas that manage stress response. Weak signals here can lead to emotional dysregulation, which in some ADHD folks can mean disinhibited aggressive impulses and oppositionality. It can result in conduct disorder, often comorbid with ADHD, and also RSD, Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria, or feeling disproportionate emotional responses to real or perceived rejection. As she gets overwhelmed, some of the folks in Brain are getting tired and emotional. They are tripping over. They are drunk-texting their boss some thoughts on the matter. They are deep-researching their ex’s new girlfriend and accidentally liking a post from 2017.

Meanwhile, at the back of the head, above the brainstem, lies the cerebellum, another part of the brain linked to ADHD. This region manages gait, balance control, coordination, and cognition. (Let’s call it Bar.) It’s development may be delayed in children and adolescents with ADHD, and research has linked low cerebellar volume with more severe ADHD symptoms in people of all ages. Poor cerebellum function may play a part in explaining why people with ADHD can experience clumsiness, balance problems, and ‘postural sway’, sometimes called the ‘ADHD walk’. If you know, you know.

Those of us with ADHD barrel into walls and bounce off cupboards, an especially troublesome symptom considering the ADHD predilection for leaving cupboard doors open.

So these are the ways that Britney the pre-frontal cortex sends the messages that keep Brain functioning. But why are her messages so scrambled? Because at its heart, ADHD is a neurochemical issue. Brain is swimming in a neurotransmitter master-stock of dopamine (which sharpens Britney’s focus and attention) and norepinephrine (which decreases the ‘noise’ that distracts her). These chemicals are the key to the signals being sent from Britney to the rest of Brain.

Too little of them and we’re tired. Too much, we’re stressed. Like that little delinquent Goldilocks (and on that: what kind of sociopath child wanders into a stranger’s house, judges the food and the décor and then goes to sleep? She definitely had ADHD. Note to self: a book assigning mental health diagnoses to fairy tale characters. Snow White’s stepmother: Narcissistic Personality Disorder. The seven dwarfs are locked in a co-dependent folie a deux, while Snow White clearly has Stockholm Syndrome. But I digress. Where were we? Ah yes- )

To complicate things further, the ADHD brain tends to recycle dopamine too efficiently through reuptake receptors. So there’s too much, or too little, or we reabsorb it into our system too quickly. Like the bears house, the chemical environment has to be ‘just right’ for the complex machinery of the brain to function properly.

On this busy night in Brain, Britney is anxious, which can sharpen her focus, but also increases the stress hormone cortisol, which suppresses the availability of dopamine. It’s a dirty circle. Britney starts moving into flight or flight, a ‘feeling’ state in which the amygdala (Drama Brain) starts driving the train and those higher-order functions get even harder to access.

Stimulant medications can adjust amounts of either either or both dopamine and norepinephrine to neurotypical levels, and also block their too-quick absorption into the system. The velvet rope is repaired, and Britney’s ability to communicate orders and block out distractions is strengthened. Now she has the knowledge, the other parts of Brain know what to do, and the orders from the clipboard are making it through loud and clear. From one dendritic spine to the next, neural messages are spat sharply and clearly down the line, so that soon Britney has Brain humming along like Studio 54 in 1980. Look, there goes Bianca Jagger riding a white horse straight to Bar!

ADHD meds are amazing. They are the most effective psychiatric meds in the brain-science world, such that ADHD is regarded by many as the most treatable psychiatric condition in the DSM5. (Sorry to brag.) But the stigma around them is pervasive, and internalised, so that many of us on meds feel slightly ashamed in a way we would not if we were just using a powerful antibiotic on our rectal fungus. Perhaps that’s a bad example.

I’ll go into my experience of taking meds in a later newsletter. But this concludes today’s armchair biology lesson! Psychiatrists, scientists and citizen-neurochemistry-boffins, feel free to spank me in the comments.

A final note. It’s hard not to speak from a certain ‘deficit’ model when talking about neurobiology and ADHD. This broken bit; this weakened system. To my mind, the ADHD neurotype is a quirk in brain structure that holds enormous value, with traits like pattern-matching, hyperfocus, creativity and compassion. ADHD is even regarded as having an evolutionary advantage for the human race.

But there is no escaping the fact that the particular functioning of a neurodivergent brain makes it harder to succeed and cope in a neurotypical world. As the old Ginger Rogers saying has it, it’s like dancing with Fred Astaire, but backwards in high hells. The social model of disability holds that problems lie not in disability itself but in a world that doesn’t accommodate difference. Thriving with ADHD requires understanding how the specific machinery of an ADHD brain can affect us, day to day. From this place, we can work on how best to live contented, healthy lives.

Share this post