Early in the NSW lockdown, I injured my back battling an afternoon gale in the Aldi car-park. Things were already tough. I was working in crisis and trauma, home-schooling three children and worrying about my elderly parents: Mum behind the firmly shut doors of a nursing home and Dad, lonely and eating his feelings with comedically outrageous meals. (A particular standout: boiled rice mixed with green curry jar sauce, topped with leftover bolognaise and drizzled with soy sauce and Kalamata olives.)

That evening, one vertebra at a time click-clacked frozen like a recalcitrant zipper as my husband Keith and I navigated six different zoom rooms over an hour, enjoying the particular hell of the 2021 high school parent-teacher conference. The school did their best, but it was a comedy of errors: this teacher sent no code, this one could not open the waiting room. Be kind! We are all in this together! I shifted my sore back and crushed my rage into a small, bitter pill. Late into the night I prepared gifts and marinated curries, trying to make tomorrow special: my beloved, steadfast Keith was turning 50 in lockdown.

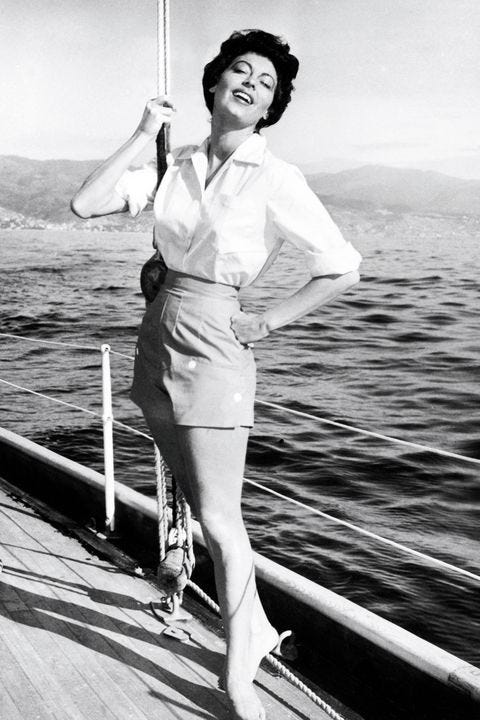

In the days that followed, I found myself turning for comfort to a 2016 reality show called Below Deck: Mediterranean, where a young, saucy crew managed demanding squillionaires on a luxurious super-yacht in various stunning locations across Croatia, France and Italy. Below Deck Med was about as far as one could get from my locked-up spine in locked-down Wollongong. It was perfect escapism.

Lockdown is a netherworld, a parallel universe in which we must observe other people from a strange, discomforting distance; and pain is very similar. As lockdown bit hard, so did my injury. I watched the complex scaffolding supporting my busy life crumble as my motor sputtered and slowed to quarter-pace.

Remote-learning life required a sharp attention, especially in the early days. I had to be ready to pivot to the most emotionally or academically needy child at any given moment; holding a steady rein with a loose hand. Whenever I could, I laid myself out like a corpse and escaped to the Med, where mask-less people leaned shockingly close to talk in restaurants and the pastel mansions of Villefranche sur-Mer spilled down the hillside to the sea.

Things fell apart as my bulging disc began to sing a high soprano. In the mornings the pain was sharp and hot as a fresh pie; by the evening blunted and blurred with painkillers. Both versions were dizzying. Keith took over kids and cooking for the few days in which I could not bear weight at all. The girls, one morning, had to help me out of the bath. In an attempt to shield them, I tried to convey ‘all fine! Nothing to see here!’ with my face. Unfortunately, this expression was over-ridden by ‘help! I am being stabbed with a BBQ fork,’ and what resulted must have been a grimace of terrifying proportions. Back in bed, I cried when I thought of their small, frightened faces. The emotional complexity of it all was as exhausting as the pain itself.

As it became increasingly clear that the NSW policy approach was moving towards ‘living with’ covid, I was terrified that I would be returned to my own difficult past of ‘living with’ chronic, disabling pain. I coped by immersing myself in a multi-episode Below Deck storyline in which the crew were furious with the chef for making onion soup for a guest whose preference sheet clearly stated his aversion to alliums. The low-stakes drama of Below Deck offered me the glorious gift of Not Being Present In The Moment.

In fact, Below Deck was unexpectedly motivating. As I recovered, I became inspired to start treating lockdown as my own tricky charter, taking seriously my role as Chief Stew. ‘All crew, all crew,’ I called. ‘Dinner is in the mess.’ I asked the children why they had not yet turned down their cabins. I scrubbed the head, did the provisioning, and managed the entertainment demands and dietary restrictions of my tiny guests.

Lockdown’s charter rolled on. 14-year-old taught herself how to make edits of her favourite Marvel moments and spray-painted the scavenged furniture she dragged to a secret spot in the bush nearby. 12-year-old recorded an avant-garde experimental jazz song called Hinky Punk; a musical mash-up of Kraftwerk, Mahler’s Ring Cycle and the Chipmunks. It was madness: lockdown in musical form. Ten year-old sewed hankies for her stuffed animals, refused to Zoom and tearily missed her friends. Even Biggles the dog was antsy, barking for an earlier dinner time every day.

As my back knitted itself back together, lockdown started to feel like the only life we’d ever had. I took work meetings in the bedroom and on Wednesdays Keith took over as Chief Stew, running the crew by his own system, while I revelled in the peaceful quiet of the converted cowshed office at the bottom of the garden. The children settled into their schoolwork. I talked to Mum on the phone, and dropped plates of dinner off to Dad, standing at the car, while from the porch he described his culinary adventures. ‘Have you heard of this pasta in ready-made sauce, Rach? Magic!’

Privilege is about having space and grace to do the small things that make life easier. As my injury healed, I was able to step outside the hot, intimate immediacy of pain and access my compassion for others who were still in that surging sea; grappling with illness and family breakdown and job insecurity. In my crisis work I talked to people experiencing different versions of this moment in time, many of them devastating, and it helped me to recognise my immense luck. Keith and I were inconvenienced and worried, but we were safe; a great good fortune that could not be understated.

We live within five kilometres of the beach, where we could watch Biggles chase a ball into the sea and surf a wave back, his seal-like black pelt slicked and his tail wagging madly above the waterline; signalling his joy at being immersed in the stinging cold, fresh Pacific. I could look far over Biggles’ exuberant tail, and imagine the Amalfi Coast, somewhere past the horizon, where life went on, super-yachts and hot tubs and disgruntled chefs and Covid and all, with the adaptability that is perhaps our greatest human superpower.

As spring unfurled, the future remained uncertain, but my bulging disc returned fully to its rightful place. The only relics left of my Below Deck binge were the single strong Moscow Mule I enjoyed at 5pm and the battery operated fairy lights I bought to enhance my tablescapes. They elevated our lockdown meals to something special, as I found myself able to see the magic in this enforced pause. This charter would end. It would. And one day, we would visit the actual Med again; foaming bougainvillea and vide-grenier markets in dusty stone villages; and the glint of turquoise water rolling out to the far horizon, timeless and lovely.

Love this Rach . Was thinking about our matching bulging disc week the other day . Seems like a lifetime ago ! Love your writing and imagery ! Xx